Here at Swiss Dental Center, Dr. Phillips and her team take great interest in modern dentistry and implementing techniques and procedures that are transforming this field. This includes but is not limited to the effectiveness of 3D Printing.

Our team takes CBCT x-rays on every patient, utilizing optical scan technology. Recent developments in CBCT has profoundly changed and revolutionized many aspects of restorative and implant dentistry.

These powerful technological tools are at the disposal of a class of individuals—dentists and dental technicians—who are often polymaths, having a broad level of creativity and an understanding of technology.

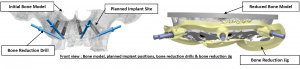

Ready access to CBCT means that it is possible for us to provide volumetric ‘image’ data to a 3D printer before surgery and to make detailed replicas of the patient’s jaws. This allows anatomy, particularly complex, unusual, or unfamiliar anatomy, to be carefully reviewed by Dr. Phillips and a surgical approach planned or practiced before surgery.

—

How Desktop 3D Printers Are Changing the Face of Facial Reconstruction

By Arvind Dilawar

“Shirley Anderson, a 68-year-old Vietnam veteran, lost the lower half of his face to tongue cancer, but a team from Indiana University has recently been able to design a new jaw for him using a desktop 3D printer. Their process, dubbed the “IU Shirley Technique,” is now being used to help other patients—representing the latest breakthrough in 3D printing prosthetics.

Anderson began the first of his treatments for tongue cancer in 1998. Through a series of surgeries and radiation therapy, he lost his tongue, jaw and Adam/s apple, rendering him unable to speak and forcing him to wear a facemask in public.

Looking for a permanent solution, Anderson and his family connected with Travis Bellicchi, a Maxillofacial Prosthodontic Fellow at IU’s School of Dentistry. Unfortunately, Anderson’s case was so severe as to be beyond the scope of traditional prosthetic techniques.

‘The prosthesis necessary to rehabilitate Shirley is larger than anything we’ve made here at Indiana University,’ explains Bellicchi in a mini-documentary about Anderson’s case, which was produced. ‘In someone’s career in my field you may never be challenged with a prosthesis of this nature.’

So Bellicchi turned to IU’s School of Informatics and Computing. ‘Travis and his colleagues are the first people in white coats to ever enter this space,’ jokes Cade Jacobs, an IU student who worked with Bellicchi. Using 3D scans of the patient, Jacobs digitally designed a prosthesis that would complement Anderson perfectly.

A prototype of the prosthesis was quickly and affordably produced on a desktop 3D printer, letting the patient be fitted in a fraction of the time and cost of traditional prosthetic methods, while still retaining the fine detail of the digital design. After the design was refined, the mold for the prosthesis was produced on the same 3D printer. This mold was then injected with silicone to create the actual prosthesis.

The IU Shirley Technique is only the latest breakthrough in the prosthetic applications of 3D printers. Although the technology behind 3D printing has existed since the late 1980s, it has mostly been used for industrial purposes by big business clients. Only in the last decade, with the rise of the desktop 3D printers, has the technology been more widely used to produce prostheses.

Amputees have benefited greatly from 3D printing’s ability to quickly and cheaply make hands, legs and feet custom fitted to their limbs, but the final products have typically looked more robotic than human. The objects produced by most desktop 3D printers can’t help but look like plastic robotic components because those printers are more adept at making K’nex parts than lifelike tissue—an obvious requirement in cases like Anderson’s.

The IU Shirley Technique represents real progress in integrating desktop 3D printers with traditional prosthetic. Similar pairings of 3D printing and traditional prosthetic techniques have been done in the past, but not with desktop printers.

This is largely due to the confluence of technological improvements and lower prices. ‘The cost of printing the mold is coming down dramatically, which is making it available to more [prosthetic] units through the world,’ says Peter Evans, a reconstructive scientist and administrator at the Center for Applied Reconstructive Technologies in Surgery (CARTIS), a partnership of Welsh hospitals and universities dedicated to advancing surgery and prosthetic innovation. When CARTIS began using 3D printers a decade ago, the machines cost around $120,000; the printer used by Bellicchi and his team was a Form 2, available for $3,499 from Formlabs, the company that produced the documentary on Anderson.”

Read more about this article here: http://observer.com/2016/06/how-desktop-3d-printers-are-changing-facial-prosthetic-design/